Copy Protection for Images & Online Media

The rise of the internet has transformed how images, videos, and documents are shared, published, and consumed. But with this convenience comes a serious risk: unauthorized copying, piracy, and plagiarism. For artists, educators, publishers, and businesses, protecting original work has become just as important as creating it. Copy protection - also known as digital rights management (DRM) or content protection – provides technical and legal frameworks to safeguard digital assets from theft, misuse, and illegal redistribution. It involves putting in place measures that actively prevent copying, rather than relying on passive notices.

This article explores the history, challenges, and methods of copy protection, with a focus on images and online media. It outlines the threats creators face and the technologies available to defend their intellectual property. In a world where a single click can duplicate a file, copy protection is essential to maintaining control over creative works.

What is Copy Protection?

Copy protection is a set of technologies, methods, and policies designed to prevent the unauthorized reproduction or distribution of digital media. In simple terms, it refers to any measure that enforces copyright by preventing copying. Unlike a basic copyright notice - which is just a legal warning - copy protection creates technical barriers that make it harder or impossible for users to copy or share content illegally. For example, a copy-protected image might be embedded in a special viewer that doesn’t allow "Save As", or a video might be encrypted so it only plays on authorized devices.

Copy protection is often discussed alongside Digital Rights Management (DRM). DRM is a broader concept covering control over access and usage (for instance, limiting which devices or how long a user can access content), whereas copy protection focuses specifically on preventing duplication of the content itself. In practice, copy protection is one foundational aspect of DRM. For example, DRM might limit how many devices can open an eBook, while copy protection ensures the eBook file cannot be duplicated or converted into an unprotected form. The two work hand-in-hand: copyright law is the legal right, and DRM/copy protection is the technical enforcement of that right.

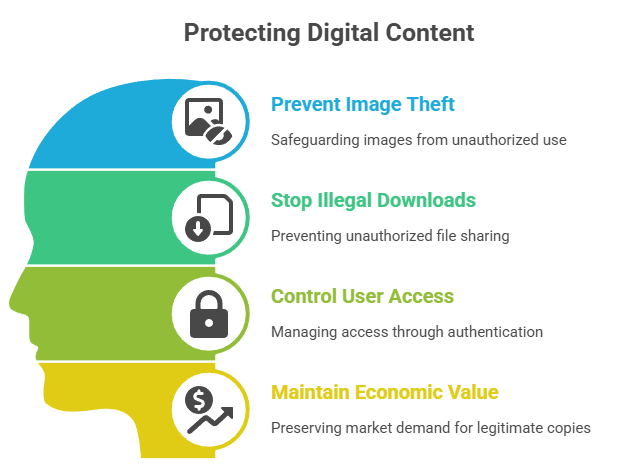

Key Purposes of Copy Protection: Some of the main goals of implementing copy protection include:

- Prevent image theft and misuse: Stopping unauthorized downloading or screenshotting of images so that artists' works or company graphics aren’t stolen and republished or sold elsewhere without permission.

- Stop illegal downloads of documents and videos: Ensuring that PDFs, e-books, or video files cannot be freely downloaded or shared on piracy sites, thereby protecting sales and subscriptions.

- Control user access through licensing and authentication: Requiring users to log in, use license keys, or be online for verification before content is displayed. This ensures only legitimate, paying users can consume the material.

- Maintain the economic value of creative works: By limiting unauthorized copies, creators and rights-holders preserve the market demand for legitimate copies. If a digital product can be infinitely copied for free, it undermines the ability to monetize it.

Copy protection measures go beyond the honor system of copyright notices. They put up actual roadblocks. A simple analogy is the difference between a "Do Not Copy" sign (copyright notice) and a lock on a file (technical protection). In the next sections, we will see why these "locks" are so important.

Why Copy Protection Matters

Copy protection isn’t just a technical concept - it's about protecting livelihoods and sustaining creative industries. Creators who spend time and resources producing images, designs, or educational materials face real threats when their work can be copied and spread to the world with a single click. Here are a few reasons why robust copy protection matters:

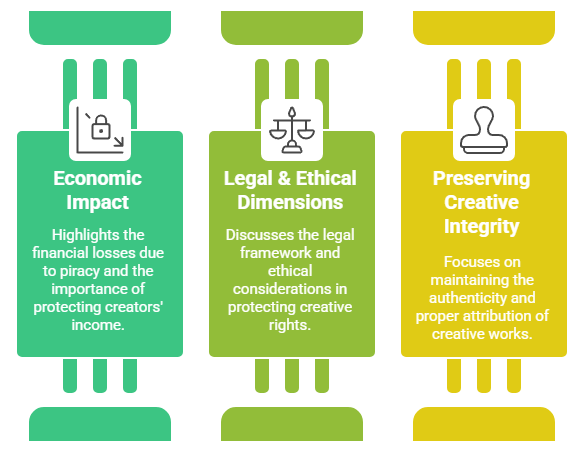

Economic Impact

Unauthorized copying directly erodes the income of creators and businesses. If someone can obtain a work for free via piracy, they won’t pay the artist or publisher. The cumulative effect is enormous. For example, global digital video piracy is estimated to cost the media and entertainment industry about $75 billion annually. In the United States alone, online piracy across all content types costs the U.S. economy at least $29.2 billion in lost revenue each year. These losses hit filmmakers, musicians, authors, software developers, and photographers alike. Fewer revenues mean less incentive and less budget for new creative works. Entire industries - from publishing to film production - are damaged by rampant piracy. By protecting content, creators ensure they can continue to earn a living and reinvest in new projects.

Legal & Ethical Dimensions

Copyright law provides a framework to protect creators (e.g. the Berne Convention and national laws like the DMCA in the U.S.), but enforcement is difficult, especially across borders and on the internet. Once a photo or video is leaked on a foreign website or a P2P network, legal takedowns become a game of whack-a-mole. Copy protection adds a technical shield that supports these legal rights by preventing the infringement before it happens. Ethically, it’s about fairness - the people who invest their creativity and money into content deserve control over how it’s used. Without protection, honest customers might pay while others get the same product for free, which is an unfair situation. By using copy protection, creators are essentially self-policing their rights, ensuring that the rules set by copyright law have real teeth in the digital environment. (Notably, laws like the DMCA even make it illegal to circumvent protection measures, underscoring how legal and technical strategies work together.)

Preserving Creative Integrity

For artists and professionals, protecting their images or videos isn’t just about money - it’s also about maintaining integrity and reputation. If an illustration or photograph is copied without permission, it might be altered or used in misleading contexts that the original artist never intended. For instance, an image could be edited and spread in a defamatory meme, or a diagram from a research paper might be used out of context to support bad science. Copy protection can help prevent such misuse by keeping the content in the controlled environment intended by the creator. It also ensures proper credit is given; when works spread freely online, often the artist's name or watermark is removed, and they lose attribution. In a protected system, it's clear who the author is and how they wanted the work presented. In short, copy protection helps honor the creator’s intentions and prevents their work from being twisted or falsely claimed by others.

In summary, copy protection matters because it underpins the sustainability of creative work. Economically, it fights the billions in losses caused by piracy. Legally, it reinforces rights in a medium (the internet) where traditional enforcement struggles. And personally for creators, it guards both their income and the authentic use of their creations.

Common Threats to Online Media

Creators face a wide range of threats when they put images, videos, or documents online. Understanding these common threats is the first step to defending against them. Below are some of the main ways content gets stolen or misused on the web:

Image Piracy

High-resolution artwork or photography can be copied and reused without permission in an instant. An artist might find their illustration reposted on someone else's website, or even sold as prints or put on t-shirts by unscrupulous vendors. Entire collections of artwork can be downloaded in bulk if images aren’t protected. For example, digital artist Brian Louma discovered that his one-of-a-kind metal fish art images were being sold on a global marketplace (Temu) by a third party without his consent. He described the moment of finding his stolen images online "like a punch in the gut". This kind of piracy not only robs creators of revenue but also exposes them to potential misrepresentation of their work.

Bandwidth Theft (Hotlinking)

Not all theft is about saving a file - sometimes other websites link directly to your hosted files. Hotlinking (also called inline linking or leeching) is when someone embeds an image or video on their site by sourcing it from your server. Essentially, their web page displays your image, but every view is actually pulling the file from your site's bandwidth. The original site owner ends up paying for the traffic while the other site reaps the benefit of the content. This is also known as "bandwidth theft". For instance, a blog might hotlink to a popular meme image hosted on another server; the blog's readers see the image, but the host server bears the cost. This can create a significant bandwidth bill or slow down the original site. It's considered bad etiquette and is akin to someone else using your resources without permission. Hotlinking can also give the false impression that the original content owner has endorsed or is affiliated with the site that’s embedding their media, which can harm the owner's brand.

PrintScreen & Screen Capture

One of the oldest and simplest ways to copy what's on a screen is the Print Screen button (PrtSc) or any screenshot tool. No matter how much you lock down an image file or a video file, if it can be displayed on a user's screen, theoretically that user can take a screenshot or record the screen. A user can simply press a key or use screen-capture software to grab an image of whatever is currently visible - be it a photograph, a frame of a video, or a page of a PDF. This method bypasses any protections on the file itself, because it copies the pixels after they’ve been rendered. It's an easy, low-tech hack that practically anyone can do. Even streaming services like Netflix, which use heavy DRM, can't prevent someone from filming their computer screen with a camera as a last resort (this concept of unavoidable capture is known as the "analog hole", meaning if you can see or hear content, it can be recorded in some form). Because of this, screen capture is a major thorn in the side of copy protection - special solutions are required to block it (discussed later in secure browsers).

Unauthorized Deep Linking

This threat is specific to documents and files. Imagine you upload a PDF or video to your website to embed it in a page. Even if you don't publicize the direct URL, someone could find the file's direct link (through browser developer tools or site maps) and then share that link or post it elsewhere. Users clicking the direct link would bypass your site's context, potentially avoiding paywalls, login requirements, or copy protections present on the webpage. For example, a paid e-learning site might host video files at a static URL; if a subscriber leaks those URLs, anyone can directly access the videos without logging in. Similarly, an "unlisted" PDF file could end up indexed by Google or shared, allowing unauthorized access. This kind of deep linking doesn’t steal the file from your server (the file is still coming from your site), but it defeats access controls and can lead to widespread distribution beyond your audience. It can also be misleading, as users accessing the file directly don’t see the original context, branding, or disclaimers on your page - they just see the raw content.

Web Scraping Bots (Spiders and Grabbers)

Automated programs known as spiders, crawlers, or website grabbers can scan websites and download large amounts of content automatically. Tools like HTTrack or SiteSucker can clone entire websites, including all images and media, for offline viewing. Malicious bots can be configured to specifically seek out media files - for instance, a bot could crawl through a photography portfolio site and download every high-res image in the gallery. These programs often ignore polite rules like robots.txt. In some cases, bots can even enumerate file names or database entries that aren't directly linked, to find hidden content. The result is that a single person running a script can steal a whole library of digital assets without ever manually clicking through pages. Such scraped content might then be republished elsewhere or compiled into "piracy packs". Because bots operate quickly and tirelessly, they pose a significant threat to online media repositories. In fact, some sophisticated bots masquerade as legitimate search engine crawlers to evade detection, or they rapidly change IP addresses to avoid IP-based blocking. This is why modern copy protection solutions are increasingly focusing on bot detection and blocking (as we’ll discuss with cloud paywalls).

Browser Features and Developer Tools

Modern web browsers are incredibly powerful - which unfortunately means they provide tools that can facilitate content theft. The simplest example is the browser's right-click context menu. By default, anyone can right-click on an image in a webpage and choose "Save Image As" to download it. They can also click "View Page Source" or use developer tools (opened by F12 key in most browsers) to inspect the HTML, find direct links to images, videos, or other files, and then download them or even manipulate the webpage's code on the fly. Browsers also have options like "Save Page As" which will download the HTML and all embedded resources (images, CSS, etc.) for offline use. A determined user with developer tools can even bypass basic JavaScript-based protections: for instance, if a site disables right-click via JavaScript, the user could disable JavaScript in their browser and then freely save images. Essentially, any content that is delivered to a standard browser can be extracted by anyone who knows how to use these built-in tools. This is why simply hiding or obfuscating content via web code is not a robust solution - a tech-savvy user can unravel it. Some particularly determined individuals use network analyzers or proxy tools to catch files in transit (as the browser downloads them) or to retrieve streaming video segments. In short, a normal browser can be an ally of the content thief. This is a driving reason behind the development of secure browsers that restrict or remove such features (more on that later).

These threats illustrate that once content is online, there are many avenues for it to be copied or accessed without permission. From casual theft (right-click saving, screenshots) to automated mass theft (bots, scrapers), a creator has to consider a whole spectrum of defenses. No single method can block all of these threats, which is why effective copy protection usually involves multiple layers of security.

Methods of Copy Protection

To counter the myriad threats above, a variety of copy protection methods have been developed. Each method has its own strengths and weaknesses, and they are often used in combination for a more robust solution. Below we discuss some of the most common and effective methods of protecting images and other online media:

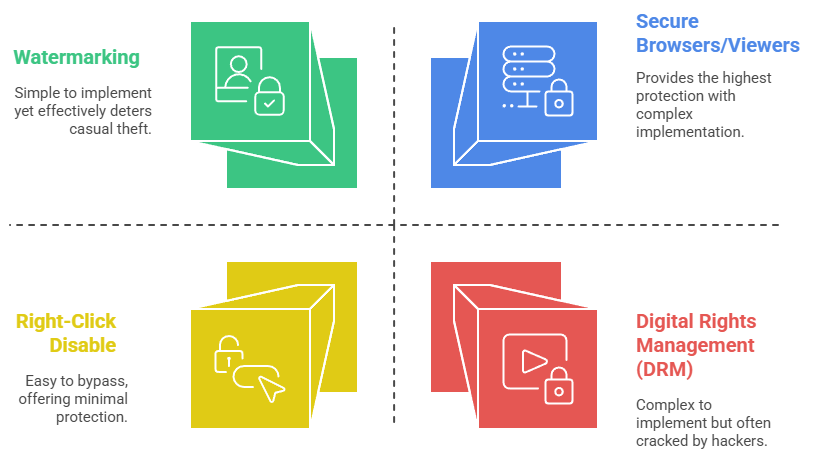

Watermarking

This is one of the oldest and simplest protective measures for images (and sometimes videos). It involves embedding a mark on the content – which can be visible, like a semi-transparent logo or text over an image, or invisible, like a digital code hidden in the pixels (steganographic watermark). A visible watermark might say "Sample" or show the photographer's name, discouraging someone from reusing the image commercially because it clearly looks like a copy. Invisible watermarks (also called forensic watermarks) don’t affect the appearance but can be detected by software to trace the source of a leak.

☑ Advantage: Watermarking is easy to implement and doesn’t require special software to view the media. Visible watermarks, in particular, make it immediately obvious who the owner is, which can deter casual theft (someone is less likely to steal an image that has a conspicuous copyright notice or logo slapped on it). Invisible watermarks, on the other hand, allow content owners to track misuse; for example, a unique invisible watermark on each distributed copy of a video can identify which user's copy was pirated if it shows up online.

☒ Limitation: Visible watermarks can spoil the aesthetics of an image or video. A big transparent logo across the center of a photo certainly protects it, but also makes it unusable for legitimate viewers except as a preview. There is often a trade-off between protection and user experience. Moreover, watermarks (even visible ones) can be removed or obscured by determined individuals - either by cropping out the watermark, using software tools to clone or fill over it, or by blurring it. Invisible watermarks can sometimes be destroyed by converting the file (like re-encoding a video, resizing an image, or printing and rescanning), although robust forensic watermarking aims to survive these transformations. In short, watermarks discourage casual theft but don't fully prevent copying or removal.

Right-Click Disable

A common tactic on websites is to use a bit of JavaScript to disable the context menu that appears when you right-click (or long-press on mobile). By doing this, site owners try to prevent the easy "Save Image" or "Copy Image Address" actions. Sometimes these scripts also block keyboard shortcuts like Ctrl+C (copy) or Ctrl+S (save). It’s a low-cost, quick fix that can stop unsophisticated users from accidentally or idly downloading media.

☑ Advantage: It stops casual theft. If a visitor was going to right-click and save your picture just because it was so readily available, now they can’t do that. The protection is immediate and works automatically on all standard images on the page. It can also signal to users that you care about your content protection; the absence of a right-click menu is a reminder that "this site doesn't want you to copy things". It may deter those who are not very tech-savvy from bothering further.

☒ Limitation: Unfortunately, this method is very easy to bypass for anyone determined (or anyone who does a quick Google search on how to save images from a protected site). A user can simply disable browser JavaScript and reload – then the right-click will function. Or they can use the browser's developer tools to find the image file. Or even simpler, take a screenshot of the image. As one discussion succinctly put it: "there are countless ways to bypass that". Thus, right-click blocking is considered a speed bump at best. It will thwart only the most casual, non-technical attempt at copying. Advanced users or bots won't be stopped at all. Because it's so weak, this method should never be the sole form of protection – it's more of an add-on layer.

Digital Rights Management (DRM)

Here we use the term in a narrower sense - the use of dedicated DRM software or systems to control access to content. DRM goes beyond just stopping copying; it can enforce all sorts of rules on how content is used. For example, a DRM-protected PDF might only open in a special reader app that checks a license, and it might forbid the user from printing or copying text from it. A DRM-protected video (like those on Netflix or Amazon Prime) is encrypted and will only play on authorized devices or apps that enforce rules like "no screen recording" and sometimes even "this stream will expire after 48 hours". DRM typically encompasses encryption, license management, and device authentication. It's a complex but powerful approach to ensure only intended users can access the content, and even those users are limited in how they can share it further.

☑ Advantage: Strong access control and flexibility. DRM systems allow content owners to fine-tune who can do what with their content. You can set up expiring access (e.g., a subscription video that vanishes after a week), or allow viewing but no printing, or allow printing but watermark the output with the user's name, etc. It's the backbone of most professional media distribution (think Kindle e-books, iTunes music, streaming media services, enterprise document systems). When done right, DRM makes it technically very hard for an average user to make unauthorized copies - the files are locked down with encryption tied to hardware or accounts. For instance, a movie purchased on Amazon is wrapped in DRM encryption; there is no straightforward way to duplicate that file in a usable form. In enterprise use, a company can send out a PDF report knowing only paying clients with the provided license key can open it - and if a client stops paying, the company can revoke their key to block further access. DRM, in theory, can provide peace of mind that even if a file is out "in the wild", it is gibberish without the secret key.

☒ Limitation: Complex to implement and sometimes user-unfriendly. Deploying DRM requires specialized software or services, integrating license servers, and often customer support for access issues. It’s not as simple as putting a watermark; you might need to choose a DRM vendor or set up infrastructure. Different DRM systems are often incompatible (a file protected with one scheme won’t open in another's player), leading to interoperability problems. For example, a song downloaded from one music service might not play on a device that isn't approved by that service. This lack of uniform standards can frustrate legitimate consumers. DRM has a reputation for sometimes punishing paying users with inconvenience while pirates find cracks anyway. There’s also an ongoing "cat-and-mouse" with DRM - many DRM schemes do get cracked eventually by determined hackers, at which point the content leaks. Managing keys and licenses can be burdensome, and if the DRM server goes down or the provider goes out of business, users might lose access to their purchases. In summary, DRM is powerful but not foolproof, and its deployment needs to be weighed against potential impact on user experience. (Notably, laws like the DMCA legally back DRM by making it illegal to circumvent it, but that also raises controversy about fair use.)

Encrypted Media Delivery

Encryption is a core part of most DRM, but even outside full DRM systems, some content owners choose to only deliver content in encrypted form. This means the image, video, or document isn't provided as a standard file that a browser can render alone; instead, it's encrypted (often on the fly) and can only be displayed by a viewer or plugin that knows how to decrypt it. For example, a video stream might be encrypted using a key so that if someone intercepts the raw data, it's useless garbage. Only the authorized video player (which has the decryption key) can play it back. Encrypted media files could be PDF files locked with a password or better, a proprietary viewer that holds the keys. The idea is that even if the files are copied, they can’t be opened without authorization. Many modern web streaming technologies use encryption under the hood - for instance, the HTML5 Encrypted Media Extensions (EME) allow browsers to play DRM-protected, encrypted video streams by obtaining keys from a license server. For images and web pages, some solutions encrypt content and require a secure browser or plugin to decrypt on the fly for viewing.

☑ Advantage: If done properly, encryption ensures that only the intended recipient can use the content. It turns the content into a locked safe - even if someone grabs the safe, they can't get what is inside without the key. Encrypted delivery is especially crucial for sensitive documents (like exam papers, confidential reports) and high-value videos (like first-run movies) where you want to minimize the window of opportunity for pirates. It can also be combined with user-specific keys so that each user's copy is uniquely encrypted (enabling tracking of leaks). Encryption also protects content in transit; for instance, it prevents man-in-the-middle attackers from snooping on a video stream. Essentially, it addresses the problem of "if they download it, they own it" by ensuring a downloaded file is unreadable without permission.

☒ Limitation: The content must be viewed in a controlled application that can decrypt it, which usually means the audience has to install something or use a specific platform. For example, an encrypted image might only display in a special photo viewer app, not in common web browsers (unless using a browser extension). This can limit ease of access – casual users might shy away if they have to go through extra steps. Also, encryption keys themselves have to be protected; if the key is exposed, the encryption becomes moot. In practice, robust encryption schemes are difficult to break, so pirates often bypass by attacking the viewing application (e.g., capturing content after it's decrypted in memory). So encryption alone, while necessary, often needs to be paired with the secure viewer environments described next.

Secure Browsers / Viewers

A more recent and highly effective approach is to use a secure viewer application - essentially a custom web browser or media player that is hardened against copying. One example mentioned is ArtisBrowser, a web browser specifically designed for copy protection. Unlike regular browsers, secure browsers can disable common avenues of content extraction. For instance, ArtisBrowser in conjunction with protected web pages will prevent PrintScreen and screen capture, disable right-click menus and shortcut keys, and even serve content in such a way that it doesn’t get cached on the disk. In other words, it operates at a system level to make sure that when you're viewing protected content, your computer simply will not allow any other program or function to copy it. Another example in the exam context is a "lockdown browser" used for online tests - it might restrict the student's computer from switching tasks, taking screenshots or seatching the web during an exam. Secure media players for video can block HDMI outputs (so you can't record via an external device easily) and resist screen recording by outputting a black screen if recording is attempted.

☑ Advantage: This method provides the highest level of protection for content because it closes the loop on the "analog hole" as much as possible. If the secure browser is well-designed, it will not only cater for encrypted content in transit, but also ensure that no copy of it remains on the user's device after viewing (no cached files, no saved images). It can prevent all the trivial copying methods: no saving, no copying text, no context menu, no developer tools, no screenshots. In ArtisBrowser's case, it even blocks packet sniffers and memory analysis - nothing can be extracted from the protected session. Essentially, the user is allowed a view only experience. This system-level protection is impossible to achieve with just a website script; it requires the cooperation of the client application, which is why a custom browser is needed. Secure browsers can also report a unique fingerprint or ID of the user's device, enabling robust DRM licensing (e.g., only a specific computer can open the file, and that ID is tracked). This greatly deters even tech-savvy pirates, because short of pointing a camera at the screen, they have no straightforward way to copy the content.

☒ Limitation: The primary drawback is user convenience and adoption. Asking users to download and use a special browser or player just to view your content can be a barrier. Some audience members may be unwilling or unable (for example, if they’re on a platform that isn’t supported - though ArtisBrowser is available on all operating systems (OS)). It also may not integrate with other web content easily; for instance, a protected page might only be viewable in the secure browser, limiting the seamlessness of your site’s user experience. There’s also an overhead in maintaining such a system (ensuring the secure browser stays updated and compatible). Moreover, while secure browsers are very effective against software-based copying, they cannot absolutely prevent someone from using an external camera to film the screen or taking a photo - though the content would never be as high quality as the original, it’s still a leak vector (albeit an analog one). Despite these trade-offs, for high-value content (like pay-per-view videos, confidential documents, art portfolios, etc.), many find the increased security worth the slight inconvenience to users who truly need the content.

Cloud Paywalls & Bot Protection

As content distribution has moved to the cloud, some sophisticated solutions have emerged that combine copy protection with access control and anti-bot measures. One such approach is the Safeguard Cloud Paywall, which not only handles payment and access rights, but also creates a secure, encrypted delivery pipeline that bots cannot penetrate. Essentially, when a human user with the proper browser (e.g., the secure ArtisBrowser) accesses the content, it's decrypted for them, but any automated agent (like a typical web crawler or an AI scraping tool) cannot get anything useful. The system may employ browser fingerprinting to ensure the client is a real, authorized browser, and not a headless scraper. Additionally, these cloud systems often maintain a whitelist of good bots (like Google's crawler) and either block all others or serve them a limited preview. They might even enforce pay-per-access for bots – for example, requiring search engines to have a special account or API to index the protected content in a controlled way (hence the "paywall" aspect, potentially charging bots or counting their access).

☑ Advantage: This is a comprehensive layered defense. It tackles the modern threat of AI-driven scraping by essentially operating in a mode where only known entities can fetch the data. For instance, the Safeguard Cloud service forms a secure tunnel to the user's desktop and encrypts pages such that only ArtisBrowser can decrypt them. All other clients (like Python scripts, cURL requests, unrecognized browsers) either get nothing or get a placeholder. This means even if a bot tries to harvest your site, it ends up with useless encrypted content. Meanwhile, legitimate users still see everything normally (provided they use the approved browser). Another big plus is the paywall integration - you can enforce monetization (subscriptions, pay-per-view) confidently because you know users can't just bypass it by crawling to a deep link (the content behind the paywall is encrypted and inaccessible without going through the front door). The mention of allowing whitelisted search engines suggests you don’t have to sacrifice discoverability; you can let Google index maybe a summary of your content while keeping full content secure for real users. Also, by blocking AI scrapers, you protect against those cases where AI services might regurgitate your text or images without credit. This kind of system is forward-looking, anticipating a web where AI bots might copy content en masse to train models or build illegal archives.

☒ Limitation: Using a cloud paywall system ties your content delivery to that particular service. There might be ongoing costs and reliance on the provider's infrastructure. There is also an adoption aspect similar to secure browsers - users might need to install a special browser or player to view content (in the Safeguard case, they need ArtisBrowser). If the paywall allows a "preview" for normal browsers and only invokes the secure tunnel for full content, the design of that preview vs full content becomes an extra step in content management. And just as with any strong protection, user convenience can be affected: casual viewers who stumble on the site might be dissuaded when asked to switch browsers or log in through the paywall. However, for content worth protecting, these may be acceptable compromises. Another aspect is that overly aggressive bot blocking can inadvertently block accessibility tools or lesser-known search engines, but such solutions can allow configuring who's allowed by whitelisting.

It is also worth noting that copy protection is an evolving field. As new threats emerge (say, a new screen-capture technology or AI that can remove watermarks), new counter-measures are developed (like more sophisticated watermarking or hardware-based encryption tied to chips in devices). Next, we'll see how different media types (images, documents, video, web pages) often demand different combinations of these methods.

Copy Protection by Media Type

Not all media are protected the same way. The optimal strategy can depend on whether you're safeguarding a photograph, a PDF report, a video, or a whole webpage. Here we break down copy protection approaches by type of content:

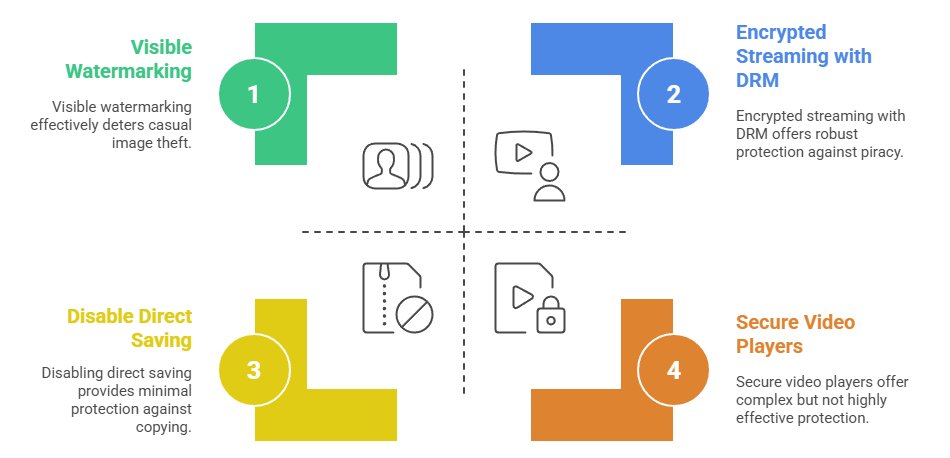

Protecting Images

Still images (photos, illustrations, infographics) are easy to copy, so protecting them is a challenge. Common tactics include:

- Visible Watermarking: As discussed, overlaying a logo, copyright notice, or pattern onto the image. Stock photo agencies (like Shutterstock or Getty Images) widely use this; they display images with a crisscross watermark of their logo. Only customers who pay get a clean image. Watermarks make stolen images less useful, because anyone who sees the image will also see it's a copy (unless the thief takes the trouble to remove the watermark, which is often non-trivial if the watermark is large or complex). For personal websites, an artist might put a small signature or URL in a corner of each image - it's modest protection, but at least if it's reposted, viewers can trace it back to the source.

- Disable Direct Saving: Many portfolio or gallery websites use scripts to disable right-click save on images. Some also layer the image under an transparent HTML element so that even if someone tries to drag-and-drop or right-click, they're actually interacting with an invisible layer, not the image itself. This provides a superficial barrier, mostly to stop immediate, casual saving of images.

- Sliced or Tiled Images: A clever trick sometimes used is to cut a high-resolution image into many small pieces (tiles) and then display them in an HTML table or using CSS so they appear as one picture. If a user tries to save, they only get a piece, not the whole image. This can foil basic scrapers and is often used by sites that want to show detail (zoomable images) but not give away the whole picture in one file. (A determined person could still retrieve all pieces and reassemble, but it raises the effort required.)

- Encrypted Image Delivery: Instead of serving a JPEG or PNG directly, some solutions deliver images through a viewer that decrypts them on the fly. For instance, an image could be embedded in a PDF or a special image viewer app which handles decryption. A more web-based approach is using a secure browser plugin that decrypts image data (which might be a scrambled base64 string in the HTML or a custom binary format) and renders it, without ever exposing a normal image file. With ArtisBrowser and ASPS, for example, the entire page can be encrypted, which includes images - only ArtisBrowser can display it. To any other browser or bot, it's gibberish data.

- Low-Resolution Previews: Some photographers only upload low-res or heavily compressed versions of images online. The high-res versions are kept offline or behind a paywall. The idea is that if someone steals the low-res image, it’s not suitable for printing or large-scale use. This isn’t exactly a technological protection, but a content strategy to mitigate loss: share enough for viewing on screen, but not enough to reproduce professionally.

By combining these methods, image owners can significantly reduce theft. For example, an online art gallery might show only watermarked, low-res images in a normal browser (with right-click disabled), but provide high-res unwatermarked images only via a secure, logged-in environment or on purchase (e.g., delivered as a time-limited download link or through a PDF that expires). It’s important to note that truly stopping screenshots of images is only possible with secure viewer apps/browsers that block that function, because the standard web browser cannot prevent someone from capturing what’s on screen. For those with extremely valuable images (like a digital art piece being sold for thousands, or sensitive satellite imagery), using a secure viewer (like an ArtistScope solution or similar) is worth considering so that screenshots come out blank and the image never hits the disk in unencrypted form.

Protecting Documents (PDFs and eBooks)

Documents such as PDF files, Word docs, or eBooks (in formats like EPUB) present a different challenge. Text content can be copied and pasted, and documents can be forwarded to others easily. Key approaches include:

- DRM with Licensing and Keys: Professional publishers use DRM-backed solutions for PDFs and eBooks. For example, Adobe has DRM for PDF in its Adobe Acrobat/Reader ecosystem; the publisher can require the user’s Adobe ID to open the file, and enforce restrictions. Similarly, eBook platforms like Amazon Kindle or Apple Books wrap the book file in encryption and require the user’s account/device authorization to open. Independent DRM providers (such as Locklizard, Vitrium, or ArtistScope's Safeguard DRM) allow document owners to distribute files that only open in a special reader app when a valid license (key or token) is present. The license can specify if the user is allowed to print, how many devices can open the file, etc. Often the document is locked to a specific user or device, preventing sharing. If a file gets out, it won’t open for others who don't have the license credentials.

- Disable Copy-Paste and Printing: Many secure PDF solutions allow the author to disable the clipboard (so text can't be copied out) and disable printing or only allow watermarked printing. Even without heavy DRM, a PDF can be created with passwords and restrictions (standard PDF has an owner password feature that can block editing or printing - though determined users can break those easily). More robust systems like CopySafe PDF take it further: this solution, for instance, uses a special reader that can block printscreen and even prevent screen-capture attempts while the PDF is open. It essentially turns the PDF into a view-only image under controlled conditions. CopySafe PDF is an example where the document is heavily encrypted and can only be opened in the CopySafe Reader (Windows application) or within a secure browser environment; it will not display at all in common PDF readers. During viewing, it stops any copying, printing, or saving of content. This kind of solution is aimed at highly sensitive PDFs (like course materials, confidential reports, or eBooks sold by niche publishers) where the publisher is willing to trade off some user convenience for security.

- Dynamic Watermarks in Documents: Another technique is to embed dynamic watermarks (e.g., "Licensed to John Doe, Transaction ID 1234") on each page of a PDF when it's downloaded by a user. That way, if the PDF is leaked or printed and scanned, it's clear which account it came from. This doesn't prevent copying per se, but it deters users from sharing their copy since it can be traced back to them. Some DRM systems do this automatically upon issuing the file.

- Expiration and Remote Control: Many document DRM solutions allow publishers to set an expiry date or remotely revoke a document. For instance, an eBook might only be readable for 30 days unless renewed. Or if a customer refund is given, the publisher can invalidate that person's access so they cannot keep reading the material. This is an advantage of digital over physical - you can theoretically "take back" content or ensure it doesn't last indefinitely on someone's drive. Of course, this requires that the document phone home or that the reader software enforces the timeline (which again points to needing specialized software).

For documents, copying can also occur by simply retyping or taking photos of pages, but those are labor-intensive workarounds. The goal of document protection is to raise the effort bar high enough that casual sharing or large-scale piracy (like posting on a torrent) is impractical. A company distributing an internal PDF manual will, for example, encrypt it, restrict it to employee devices, and perhaps even embed each employee's ID on each page. That way, if it leaks, they know who leaked it, and hopefully it wouldn't open for outsiders anyway. In the consumer space, PDF-based reports or eBooks sold directly by authors can be protected by third-party DRM services so that even if the PDF is forwarded, it won't open without the right key.

In summary, yes, PDF can be copy-protected effectively - but it usually involves using special software or services beyond just the default PDF format. CopySafe PDF is one such specialized tool that prevents copying, printing, and screen capturing of PDF content. Enterprise DRM systems achieve similar outcomes with more integration and cost. Without these, a PDF is just data that can be easily duplicated, so relying on just a password or a disclaimer is not sufficient if the content is sensitive.

Protecting Video

Video is one of the most pirated forms of media, and the industry has developed robust methods to protect it, especially for streaming. Approaches include:

- Encrypted Streaming with DRM: Almost all major streaming platforms use adaptive streaming with encryption (such as HLS with AES encryption, or MPEG-DASH with Widevine/PlayReady/FairPlay DRM). In these systems, the video file is broken into small segments, each encrypted. When a user presses play, their player device contacts a license server to get decryption keys (after validating their rights). The player then decrypts and plays each segment on the fly. If someone tries to directly access the video files, they’re encrypted. And because the keys are delivered securely to certified players (often leveraging hardware security on the device), it's difficult for an outsider to intercept them. DRM for video can also enforce limitations like HDCP requirement (to prevent recording from HDMI outputs), or restrict whether you can download for offline, etc. For example, Netflix, Disney+, Amazon Prime - all use such DRM encryption (Google Widevine or Microsoft PlayReady or Apple FairPlay) to ensure that even if you sniff the network traffic, you can't reconstruct a watchable video. These systems are quite effective; large-scale piracy of such streams usually happens either via stolen credentials (people pointing a camera at a screen or using a compromised device to capture raw output) rather than breaking the encryption.

- Watermarking (Forensic and Visual): High-value video content like screener copies of movies or live sports streams often include forensic watermarks. If a pirate records the video and re-uploads it, the watermark (invisible to normal viewing) can be extracted to identify which subscriber or session it came from. This has become a standard in Hollywood - for instance, HBO or Netflix could trace a leaked episode to a specific user account or distribution channel via forensic watermarking. Some live sports broadcasters are even able to shut down pirate streams mid-game by quickly extracting watermarks from the pirate stream and identifying the source subscription to cut off. Additionally, some services show on-screen visible watermarks for pre-release copies (like the recipient’s email or an ID) to deter sharing. These don't prevent copying but deter it and aid legal enforcement.

- Secure Video Players: On computers, a secure player like CopySafe Video can be used for delivering video files that need protection. CopySafe Video, for example, encrypts video files and they can only be played in the CopySafe player or within a controlled browser (ArtisBrowser). While playing, it blocks screen capture and does not allow saving the raw video. It's analogous to the PDF solution but for video. This is useful for training videos, confidential corporate videos, or indie content distribution where the content owner has more control over the playback environment. Additionally, newer secure players may use watermarking and device binding as well.

- Streaming Platform Controls: Beyond encryption, streaming services apply other tactics: limiting resolution on unsecured outputs (Netflix won’t stream 4K to a device unless it's HDCP 2.2 compliant, because 4K is easier to rip in full quality otherwise), using short key rotation (so even if one key is compromised, it only decodes a few seconds of video), and quickly responding to takedown requests for pirate links (not prevention, but a mitigation).

Protecting video is often about balancing quality and security. The highest security is obtained when using a custom application that has total control (like a proprietary secure player). But most consumers prefer using their convenient devices and apps, so the industry has focused on DRM standards that integrate into common devices while still providing strong protection. The result is that casual piracy (like simply downloading a video file from a streaming site) is no longer possible; it requires specialized ripping tools and often a bit of hacking. Still, as we all know, popular shows and movies do get pirated - usually by attackers who either exploit a weak link (like an Android device with older security, or using screen-recording hardware). From the content owner's perspective, the goal is to make piracy hard and inconvenient, reducing its prevalence. And indeed, piracy rates dropped in sectors where easy legal access was provided under DRM (though it's creeping up again with content fragmentation).

To summarize: securing video relies on encryption and controlled playback environments. A combination of DRM, possibly hardware support, and watermarks is used to lock down video. For those distributing video on their own (like a company selling training videos), products like CopySafe Video can wrap the videos with DRM and ensure they only play in a protected environment. No solution can guarantee 100% that a determined pirate won't find some way (even if pointing a camcorder at a screen), but these methods dramatically curb easy, high-quality piracy.

Protecting Web Pages

Sometimes the thing you want to protect is not just a media file, but the content of an entire webpage - HTML, text, designs, or web-app functionality. This is particularly relevant for online courses, secure data portals, or paywalled articles. Key methods include:

- Site-wide Encryption (Secure HTML): A technology exemplified by ArtistScope's ASPS (ArtistScope Site Protection System) essentially encrypts the web page content on the server and only a secure browser can decrypt and display it. This means if you visit the page in a normal browser, you will see nothing or junk data, whereas ArtisBrowser will decrypt and show the intended page. The encryption happens on the fly, and it covers everything in the page - text, images, videos, etc. To the user in ArtisBrowser, it looks normal (except with all copy functions disabled), but to any other agent, it's impenetrable. This is a very high level of protection for web content. For example, a membership-only knowledge base could use this so that even if a member shares the page URL, outsiders cannot view it without the correct browser and permissions. It also stops scrapers because they only get the encrypted content. Essentially the webpage becomes a secure container.

- Disabling Browser Features (in regular browsers): While a regular browser cannot be fully controlled, some web developers try to disable certain features via code. For instance, you can attempt to block the F12 key (Developer Tools) with JavaScript, or detect if Dev Tools are open and then obfuscate/hide content. You can also disable text selection (so people can't easily copy-paste text) via CSS/JS. These tricks are security by obscurity -a determined user can find ways around them (there are even simple ways to prevent the detection of Dev Tools). Nonetheless, for some situations like preventing casual users from viewing the source or copying text, these methods add friction.

- Login Walls and Session Control: A simpler part of protecting pages is of course to put them behind a login and not allow search engines to index them. Then use session tracking to ensure one login isn't being used by multiple people at the same time (some systems will auto-logout other sessions if the same user logs in elsewhere). This doesn’t prevent copying of content by the authorized user, but it does keep out unauthorized users. It's the first line of defense: make sure only auhorized viewers get to see the content. From there, you add on the above methods to control what those viewers can do (like not copy).

- Prevent Caching: Sometimes developers use meta tags or headers to tell browsers not to cache pages or images. This way, there isn’t an easily accessible file saved that someone can dig out of their cache folder. It's a minor protective measure (since one could just save the page manually), but it can help ensure if someone exits, they can't read the page offline later without logging in again.

- Blocking View-Source via Settings: Modern browsers don’t allow a site to outright block the user from using developer tools or view source. However, when using a secure browser like ArtisBrowser, those features are inherently off for protected content. In a controlled enterprise scenario (like on a company-provided device), IT admins might configure policies that disable the browser's ability to save pages or use dev tools for certain sites. But that's not common for consumer scenarios.

In practice, the most secure way to protect a webpage is to require it to be opened in a secure browser or environment. If one insists on using standard browsers, you rely on obscurity (minifying code, disabling right-click, etc.) which only guards against mild curiosity, not real attacks. Some publishers use a hybrid approach: e.g., an online textbook might show most content in a normal web interface but particularly sensitive diagrams or data tables might be shown via a secured iframe that only loads if a certain plugin or condition is present – otherwise it doesn’t display. That way, even if a student tries to inspect the HTML, the key info isn’t there unless the content protection plugin delivered it.

Disabling developer tools in a general browser is not truly possible, but secure browsers by design have no such tools available to the user. They essentially turn a web page into a kiosk-like application – you can view and navigate, but you can’t poke under the hood.

To summarize, protecting web pages often means treating the whole page as protected content, not just pieces of it. Encrypting the page and requiring a special viewer like ASPS/ArtisBrowser is a top-tier solution for that. Short of that, standard web techniques can hide or guard content to a limited extent, but a savvy user can always retrieve what the standard browser has to display (because by design, browsers give users the keys to view the content, which means they can also copy it unless prevented externally).

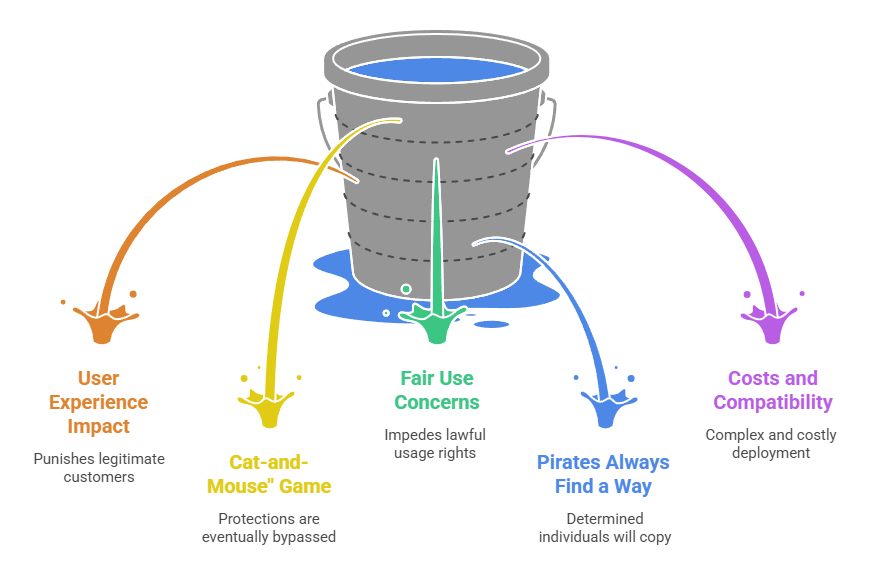

Criticism & Limitations

While copy protection is essential from the creator's perspective, it's not without controversy and challenges. It's important to acknowledge these, as they highlight why copy protection must be carefully implemented and continuously improved:

Impact on User Experience

One common criticism is that certain copy protection measures inconvenience or punish legitimate users. For example, heavy-handed DRM can mean that a customer who bought a movie can't easily watch it on their other devices, or an eBook might not let a paying reader copy a quotation for fair use in a review. There have been notorious cases, such as DRM on music that prevented shifting songs between devices, which led to customer backlash. Even watermarks and disabled right-clicks can frustrate honest users (perhaps someone who bought an image legitimately but finds the watermark annoying until they get the final file, or a user who wants to quickly lookup something by copy-pasting text but the site blocks it).

Historically, certain CD copy protections even installed hidden drivers ("rootkits") that caused security issues on users' computers - a PR disaster in the mid-2000s. Striking a balance is tricky: too lenient and piracy runs wild; too strict and you drive customers away or impair usability. As a result, some companies have eased up on DRM for music and software, relying more on services and goodwill. Nonetheless, industries like video and publishing still rely on DRM because the risk of unfettered copying is deemed greater than the downsides. The key is to design protections that are as transparent as possible for legitimate users. For instance, many subscription streaming services have DRM that most users never even notice – it works in the background, while they continue to stream on authorized devices seamlessly.

Cat-and-Mouse and Workarounds

As noted earlier, no copy protection is 100% unbreakable. History has shown that determined hackers or pirates eventually crack or find a way around many protections. A famous quote from an IBM PC pioneer, Don Estridge, regarding copy protection was: "I guarantee that whatever scheme you come up with will take less time to break than to think of it." - en.wikipedia.org. While that might be a bit of hyperbole, it reflects the reality that the adversary only needs to succeed once. For example, every major DRM (from DVD's CSS to Blu-ray's AACS to various game protections) has eventually been broken or circumvented by someone. New protections come out, and then new cracks appear – it's an ongoing arms race.

Additionally, many protections can be bypassed by "analogue" means as discussed: screen-recording a video, photographing a screen, retyping text, etc. Pirates also share tips: if a site uses right-click blocking, a quick web search shows how to get around it; if a PDF is password-protected, there are free tools to strip out those passwords (since the PDF encryption for owner password is not very strong in older versions). Moreover, piracy organizations operate professionally, especially for software and video games - they use debuggers and custom code to remove DRM checks and then distribute "cracked" versions widely. From a pirate's point of view, they see themselves as providing a service (albeit illegal) by freeing content from restrictions. For content that has mass appeal, you can almost expect someone will try to pirate it. This is why copy protection is often about delaying and dissuading. If it takes pirates a long time to crack something, the content has more time to earn revenue in the crucial early window (e.g., opening weekend of a movie, or initial release of a software). If it's too difficult, many would-be pirates won’t bother at all or won’t have the expertise.

DRM and Fair Use / Ownership Concerns

On the consumer rights side, there's criticism that DRM and copy protection can overreach, impeding lawful usage. For instance, U.S. law allows format-shifting or backups of media you own, but DRM might prevent you from making a backup copy of a DVD you bought. It can also conflict with accessibility (screen readers for the blind might be blocked from reading an eBook due to DRM restrictions). Over the years, consumer advocacy groups have pushed back, and we've seen some changes: e.g., music is now mostly sold DRM-free (iTunes dropped DRM in 2009 for songs) because the industry realized it was alienating paying users more than stopping pirates (who had many DRM-free MP3s available).

The DMCA's anti-circumvention clause (and similar laws worldwide pursuant to the WIPO Internet treaties) make it illegal to break DRM, which means even for a legitimate purpose (like wanting to excerpt a short clip for a parody, which is fair use), one is in a gray area if they have to crack DRM to do it - thembj.orgthembj.org. This has raised ethical and legal debates. Some content producers respond by providing legal alternatives for common needs (e.g., a way to obtain a license for educational use of clips, or providing some DRM-free options for archival by libraries). The bottom line is that copy protection, if too restrictive, can feel like it's treating customers as potential criminals, which is an image creative businesses have to manage carefully.

Pirates Still Find a Way

Despite all efforts, there's an acknowledgment in the industry that a determined individual will always be able to copy given enough time and skill - en.wikipedia.org. The aim is to stop casual and bulk infringement, not a targeted one-off copy. For example, no copy protection can prevent someone from manually writing down or transcribing a text by hand, or painting a replica of an image, etc. It’s just important to remember that copy protection raises the bar, but it doesn't create an impregnable fortress. This is why legal enforcement and education remain parts of the strategy too - to handle the cases where technology fails.

Costs and Compatibility

Implementing strong protection might involve extra costs - licensing DRM technology, higher bandwidth (for encrypted streams with overhead), customer support for users who struggle with the secure system, etc. Smaller creators might find it too costly or complex to deploy enterprise-grade protections. Additionally, compatibility issues (e.g., a certain DRM isn’t supported on Linux, or a secure browser isn’t available on older devices) can exclude some potential audience. This can limit the reach of the content or require maintaining parallel versions (protected and unprotected) for different users, which is a hassle.

However, despite these criticisms, doing nothing is usually worse for creators who rely on content sales. If you put out a high-value piece of content with zero protection, it can be copied infinitely with minimal effort, and you have essentially no recourse except chasing individual infringers after the fact. That's why most professionals opt for at least some level of protection. The ideal approach is a layered one: combine legal, technical, and user-engagement strategies. For instance, use technology to thwart mass copying, use legal notices and watermarks to scare off casual theft and claim your rights, and use a good user experience to entice people to buy or subscribe rather than seek pirated versions.

In essence, copy protection is a defensive game. It buys time and effort. The hope is to make piracy not worth the trouble for most people, while keeping honest customers happy. It’s also continually improving - for example, modern solutions using AI might detect piracy as it happens (like monitoring if your content appears on the web illegally) and automate takedown, adding another angle to fight piracy beyond just prevention.

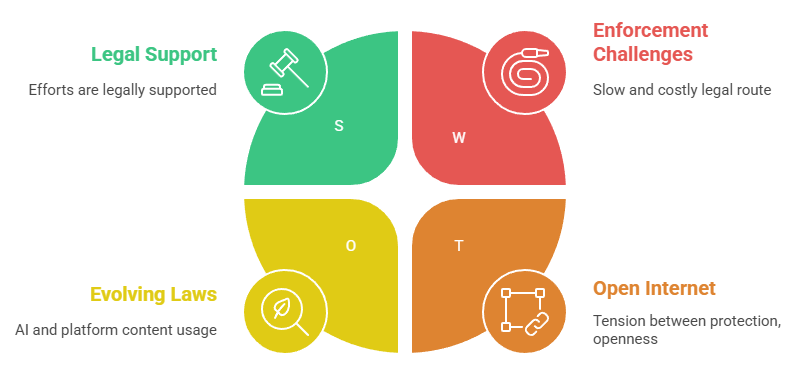

Law & Regulation

Copy protection technologies are reinforced by legal frameworks. Copyright law itself gives creators exclusive rights to reproduce and distribute their works, and various international treaties and national laws provide additional tools relevant to digital protection. Some key legal pillars include:

Berne Convention (1886)

This is the foundational international treaty on copyright. It established that creative works are automatically protected by copyright in all member countries as soon as they are "fixed" in a tangible form, without the need for registration. The Berne Convention introduced principles like national treatment (each country gives foreign authors the same protection as its own) and set minimum standards for protection (e.g., duration of copyright, exclusive rights). It’s often called the cornerstone of international copyright law. While the Berne Convention doesn’t specifically mention digital copy protection (given its era), its philosophy underpins modern law: authors have the right to control copying of their works. Thus, using copy protection is one way authors exercise their Berne-given rights in the digital domain. Essentially, Berne ensures if someone in another country tries to copy your work, you still have legal rights there (important when pursuing international piracy cases).

DMCA (1998) - Anti-Circumvention

The U.S. Digital Millennium Copyright Act is notable for its Section 1201, which made it a violation to circumvent technological protection measures used to protect copyrighted works. In other words, not only is unauthorized copying illegal, but trying to break DRM or distribute DRM-cracking tools is also illegal in the U.S. (with some exceptions carved out later for things like encryption research, accessibility, etc.). This was a major support for copy protection - it gave teeth to DRM by putting legal penalties on breaking it. Other countries implemented similar rules due to the WIPO Internet Treaties (WCT and WPPT).

The DMCA also includes the "safe harbor" provisions for online service providers (ISP/platforms) which is why we have the notice-and-takedown system for infringing content online. But from a copy protection standpoint, the DMCA's message was: those locks on digital content are backed by law. If a hacker breaks DVD encryption and uploads the method (as happened in the famous DeCSS case for DVDs), they could face legal action beyond just copyright infringement - because they broke a protection measure. While this has been controversial (critics argue it can impede legitimate fair uses, as mentioned), it's undoubtedly a boon for rights-holders in deterring open trafficking of DRM-cracking tools. For example, a company selling a tool that removes ebook DRM can be sued under anti-circumvention laws. This legal threat helps to keep the ecosystem of copy protection somewhat secure (though the tools still circulate underground).

WIPO Copyright Treaty (WCT, 1996)

An international treaty negotiated by members of the World Intellectual Property Organization to address digital technology. The WCT, along with the WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty (WPPT), explicitly called for member countries to provide legal protection for technological measures used to protect works. This is why many countries after 1996 updated their laws to include DMCA-like anti-circumvention rules. The WCT basically modernized copyright law for the internet age, affirming that computer programs and databases are protected and that authors have rights over digital distribution and communication to the public. Importantly, it obliged signatories to outlaw the removal or tampering of digital rights management information and to prohibit circumvention of TPMs (technological protection measures). So, the DMCA was the U.S,'s implementation of those treaty commitments. The WCT strengthens authors' rights in the digital environment by ensuring that international law recognizes things like DRM and requires countries to help combat their circumvention.

Other Relevant Laws

There are numerous national laws and regulations that touch on copy protection. For example, the EU Copyright Directive (and later the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market) also has provisions about TPMs and rights management info. Laws like the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (in the U.S.) can sometimes be used against extreme cases of system hacking to steal content. On the flip side, consumer protection laws can influence DRM (like requiring sellers to inform consumers that a product has DRM, etc.). Additionally, copyright laws usually have enforcement mechanisms (civil and criminal) for willful infringement at a commercial scale - which is relevant when going after organized piracy operations.

What these laws mean for a creator using copy protection is that your efforts are legally supported. If someone tries to hack your protected content, you might have legal grounds not just on copyright infringement but also on violating anti-circumvention statutes. It also means you can send DMCA takedown notices to websites hosting pirated copies, and they're compelled to comply or face liability. However, the legal route can be slow and costly, especially across borders (shutting down a pirate site hosted overseas can be very difficult even with treaties, as jurisdictions differ in enforcement enthusiasm). Thus, legal frameworks are a crucial backup, but not a standalone solution.

One should also note that laws are evolving. The conversation around how AI and internet platforms use content is ongoing - for instance, some jurisdictions are considering if platform moderation or filtering (so-called "upload filters") should be mandated, which effectively could act as a copy protection at the platform level by automatically blocking uploads of copyrighted content. There's tension between protecting creators and maintaining an open internet, and legislation is trying to keep up.

In conclusion, laws provide the context and consequences for copy protection. The Berne Convention set the stage by giving you rights globally. The WIPO treaties and DMCA gave you tools to legally protect the digital lock you put on your work (by making it illegal to break that lock). But using those laws usually comes after a breach has occurred (to punish or seek damages). Copy protection technologies aim to prevent the breach from happening in the first place. Combined, they form a more complete defense - tech measures to stop most users, and legal measures to go after the truly determined infringers and to deter would-be hackers by the threat of fines or jail.

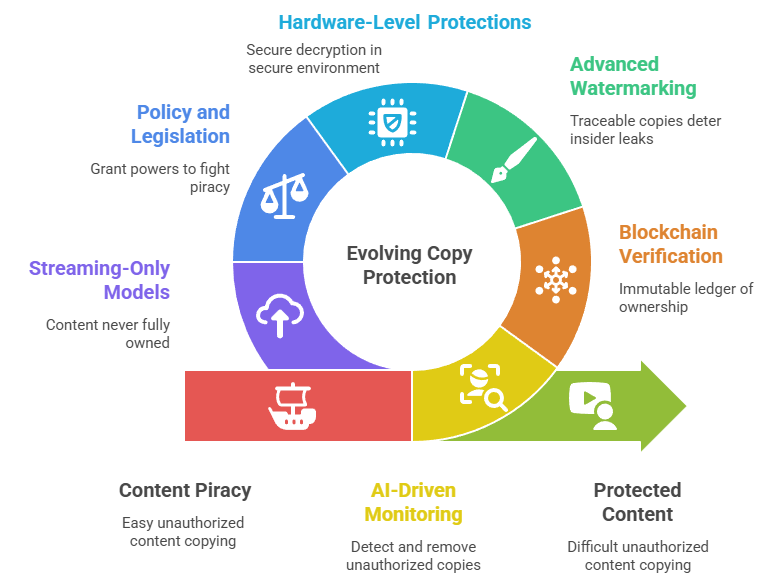

Future of Copy Protection

As technology advances, both the methods of piracy and the methods of protection continue to evolve. The future of copy protection will likely be shaped by a few key trends and emerging technologies:

AI & Machine Learning – Double-Edged Sword

AI is becoming a factor in both content theft and content protection. On the threat side, AI can scrape and aggregate content faster than humans (for example, using machine vision to recognize and extract images, or language models to summarize or reword text content, potentially undermining the original). There are already cases of AI being used to mimic art styles or "copy" artwork - for instance, AI models trained on thousands of images can produce new images in a particular artist's style, raising concerns about a new form of intellectual property leakage. Web scraping bots are getting smarter thanks to AI, able to navigate sites like a human and bypass simple bot detection. On the defense side, the same technology can help protect content. AI-driven monitoring tools can crawl the internet on behalf of rights-holders, looking for copies of images or videos (using image recognition or watermark detection) and automatically issue takedown requests or alerts.

Machine learning can also be used to distinguish human user behavior from bot behavior with greater accuracy, helping to block unauthorized scraping. For example, some modern anti-bot systems use behavioral analysis (mouse movements, timing, etc.) to identify likely non-human visitors. We might also see AI that can dynamically alter content in a way that’s imperceptible to humans but confuses AI models (a kind of adversarial approach) - imagine an image subtly modified so that an AI scraping it gets "poisoned" data or cannot properly identify it, whereas a human sees it fine. In summary, AI is an arms race: just as bots might use AI to evade detection, copy protection will employ AI to catch them. (As a real-world note, the Safeguard Cloud solution explicitly mentions blocking "AI and other bots" and viewing their scraping as plagiarism/exploitation – showing that providers are already positioning against AI content miners.)

Blockchain and Decentralized Proof of Ownership

Blockchain technology offers an intriguing potential for copyright and copy protection in terms of verification and tracking. While blockchain can't stop someone from copying a file (it's not a DRM mechanism itself), it can serve as an immutable ledger of ownership or licenses. For instance, a digital artwork could be registered as a non-fungible token (NFT) on a blockchain, creating a public record of who owns the "original". If someone tries to sell a copy, buyers could check the blockchain to verify authenticity. Some startups have explored blockchain-based DRM, where decryption keys are managed through a blockchain ledger - ensuring that only the rightful purchaser's wallet has the key, etc. Another use is timestamping and rights registry: creators can timestamp their work on a blockchain to prove it existed at a certain time and that they are the creator, which helps in legal disputes and deters others from claiming the work. Blockchain might also enable new distribution models that inherently track usage (for example, micro-payments via smart contracts every time a piece of content is accessed, with transparency).

However, blockchain's effectiveness depends on adoption - it works well for proving ownership, but it doesn't physically prevent copying. It's best seen as a complement: it can protect the integrity of ownership and licensing information. If in the future major platforms or operating systems integrate DRM with blockchain, we could see, say, a movie file that only plays if a blockchain says this user’s account owns a valid token for it – if they transfer the token (sell the movie second-hand), the file might become playable for the new owner instead (something not easily done with current DRM). This could even address the common complaint that buying DRM content isn't like buying a physical good (you can’t resell or lend it) by allowing controlled transfers via blockchain.

Advanced Watermarking and Fingerprinting

Watermarking technology is expected to become even more sophisticated. Invisible forensic watermarks might be made more robust through AI - e.g., watermarks that adapt to the content in a way that's harder to detect or remove algorithmically, and that survive compression, filtering, or even partial captures of content. We're already seeing this in video: companies like Nagra and Verimatrix have watermark tech that can pinpoint a subscriber within minutes of a live sports stream being pirated. In images, future watermarking could embed information not just about the owner but about the authorized recipient.

For instance, when someone views an image, a unique watermark could be applied on-the-fly tied to that session or user. If that image is screenshotted and leaked, the origin can be traced precisely (this requires the viewing app to do the watermark injection). Similarly, fingerprinting (identifying content by its inherent traits) is getting better - content recognition systems might automatically flag uploads of copyrighted content even if altered (we see basic versions of this in YouTube's Content ID for music/video). In essence, the goal is to make every copy traceable. If pirates know any leaked copy can phone home who it came from, it may dissuade insider leaks and subscription sharing leaks.

Hardware-level protections

Future devices may incorporate more DRM at the hardware level. We already have TPM (Trusted Platform Modules) and secure enclaves in CPUs and mobile chipsets that handle encryption keys securely. As piracy attempts get more sophisticated, content providers may lean on hardware root-of-trust to ensure their media can only be decrypted in a secure environment. For example, 4K Blu-rays mandate that the player's hardware has a secret key and that key exchange happens in an encrypted chip, etc. We might see PC graphics cards with enforced DRM pipelines (some GPUs already support HDCP and other content protections). If future operating systems and hardware collaborate more, we could have, say, a PC where you can only view certain protected content if your monitor, OS, and CPU all have a certified chain that prevents screen capture. (This exists partially with things like Microsoft's Protected Video Path.) Of course, this raises issues about consumer freedom, but from a pure technical standpoint, tying content to hardware makes it much harder to intercept illegally.

Policy and Legislation Developments

As mentioned, laws might evolve to grant more powers to fight online piracy (or in some cases, to curtail overreach of DRM - it can go both ways). There's discussion about maybe making big internet platforms more responsible for policing copyrighted content (upload filters, etc., as seen in recent EU directives). If that becomes widespread, it could act as a strong copy protection in practice (imagine if any pirated image uploaded on a social network is automatically recognized and blocked - that would be a boon for photographers). On the flip side, there's also a movement for allowing more exceptions to anti-circumvention for legitimate purposes (like right-to-repair, or fair use for educators). By 2025 and beyond, we might find a new equilibrium where content protection is strong, but with more nuance allowing non-infringing uses.

Dynamic Content and Streaming-Only Models

We may also see more content delivered in ways that it's never fully "owned" by the user. For example, instead of selling downloadable files, more content might be kept server-side and only streamed on demand in a controlled viewer (much like how Netflix streams movies – you never get the movie file itself). Even software is moving to cloud-based (SaaS models) to avoid local copies that can be cracked. If bandwidth and connectivity keep improving, the need to give users a downloadable copy lessens. This trend inherently protects content - it stays on the server, and only ephemeral data is sent. Of course, streaming can be captured (screen recording), but again i'’s about raising the skill threshold required.

In summary, the future will likely bring stronger integrations of copy protection into the fabric of how content is consumed. The ideal (for rights-holders) is a scenario where any attempt to use content in an unauthorized way either fails technically or is immediately identified and traceable. We are moving closer to that with holistic systems like secure hardware, cloud distribution, and smart watermarking. At the same time, pirates will undoubtedly find new exploits, and new platforms (like maybe VR/AR content or 3D printing designs) will open new fronts for the copy protection battle.

Ultimately, copy protection must continuously adapt to remain effective. As one side innovates, the other counters - it's an ongoing cycle. But with responsible use and improved technology, the hope is that most consumers will choose legal, convenient access, and piracy will be relegated to a smaller, more hard-core group. If nothing else, the existence of robust copy protection pushes the industry to come up with better legal services (since they know simply selling a file without added value won’t cut it in a piracy-filled world). In that sense, the future might also see more creative business models (subscription bundles, interactive content, patronage systems) that complement technical protection.

FAQs

1. What is the best way to protect images online?

The strongest protection for images is to use a secure viewing method that prevents saving and screen capturing. This often means delivering images through an encrypted viewer or a specially designed secure browser rather than as standard files. For example, solutions like the ArtisBrowser (with ASPS) display images in a way that they cannot be copied or even screenshot by the viewer. These browsers operate at the system level to block functions like PrintScreen. In practice, a combination of measures works best: watermark your images (to deter re-use), only publish web-resolution versions, disable easy saving in the webpage, and if the content is premium, consider a proper image DRM or secure gallery that uses encryption. While no method is foolproof against someone determined (they could take a photo of the screen), using a secure delivery system makes it extremely difficult for anyone to grab a high-quality copy of your images. In short, embedding images in a protected viewer (or app) with encryption and screenshot-blocking is the best available protection for highly valuable images.

2. Can watermarks stop image theft?

Watermarks can discourage image theft, but they don't prevent it. A visible watermark (like a logo across the image) will make many people think twice about stealing the image for their own use because it's obvious and usually undesirable to have someone else's watermark on it. Casual users might move on to easier targets that aren't watermarked. However, watermarks do not fully prevent copying. They can be removed with effort - either by cropping the image, editing it out in Photoshop, or using AI tools that can now do content-aware fills. Invisible (forensic) watermarks won’t deter a thief (since they can't see it), but they can help identify the source of a leak after the fact. In summary, watermarks are a useful deterrent for casual theft and a tracking mechanism for leaks, but a determined infringer can circumvent or ignore them. Many professionals use watermarks as one layer of protection, then rely on other measures if stronger security is needed.

3. How does DRM differ from copyright?